Home / PFAS

PFAS

PFAS is the name for a group of thousands of manufactured chemicals that do not naturally occur in water. The Environmental Protection Agency will regulate a group of PFAS chemicals and Louisville’s drinking water meets these new standards.

Learn more about PFAS chemicals and what we’re doing to limit their occurrence in our drinking water.

What Are PFAS Compounds and Where Do You Find Them?

PFAS or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are a group of manufactured chemicals that do not naturally occur.

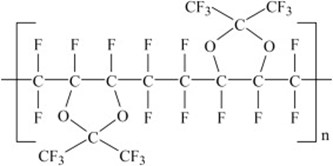

Since the 1940s, PFAS chemicals have been used in industry and consumer products worldwide. PFAS contain chains of carbon and fluorine atoms linked together. These carbon–fluorine bonds are strong and do not easily break down, which make them useful for many products, such as nonstick cookware, water-repellent clothing, stain-resistant fabrics and carpets, cosmetics, firefighting foams, and products that resist grease, water, and oil. Perhaps the best-known PFAS is polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which also goes by the brand name “Teflon,” trademarked by the DuPont Company in 1945.

What Do Scientists Know about Exposure to PFAS?

Due to their widespread production and use, as well as their ability to move and persist in the environment, surveys conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that most people in the United States have been exposed to some PFAS. Most studies indicate that exposure to PFAS chemicals from drinking water represents a small percentage of our overall exposure. The substantial exposure to PFAS chemicals is from other consumer goods. However, through manufacturing and consumer goods, PFAS can travel into the soil, water, and air. Since most PFAS do not break down, scientists detect PFAS chemicals in rivers, lakes, and groundwater.

In the mid-2000s, following research that indicated there may be health concerns with low-level exposure to two PFAS chemicals, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), some manufacturers voluntarily phased out the chemicals from production. However, PFOA and PFOS are persistent; they are long-lasting, and their components break down very slowly.

New forms of PFAS are constantly being developed. For example, hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA) and its ammonium salt are also known as “GenX chemicals.” GenX is a trade name for a processing aid technology used to make high-performance fluoropolymers without the use of PFOA. Likewise, perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS) is considered a replacement for PFOS.

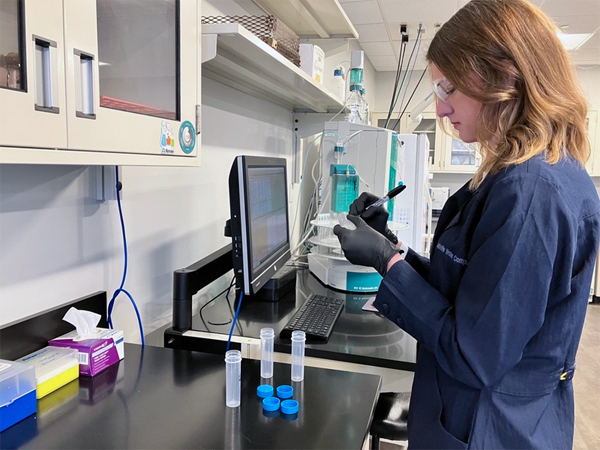

What Do Louisville Water Scientists See?

Our research indicates PFAS levels in our water that are below EPA proposed standards.

Since 2013, Louisville Water has monitored the Ohio River, groundwater, and finished drinking water for a group of PFAS chemicals. Over this time, technology has improved allowing our scientists to test for PFAS at lower concentrations. Right now, we sample at parts per trillion (ppt). For perspective, one part per trillion is equal to one second in 32,800 years or one drop in 20 Olympic-size swimming pools.

We sample quarterly and report the running annual averages for a group of PFAS chemicals. Of the PFAS chemicals we sample, we only detect PFOA. You can see the complete data set here.

What is Louisville Water Doing to Reduce PFAS Levels?

Even though our current research shows levels of PFAS that are below the EPA’s proposed regulation, Louisville Water wants to do more to further reduce these small amounts.

PFAS travels into the Ohio River from a wide range of activities: manufacturing facilities producing or using products containing PFAS chemicals, publicly owned wastewater treatment plants, urban and even agricultural runoff. Louisville Water continues to research advanced treatment options to reduce levels even lower than what we currently detect. One of the options we are evaluating is using powdered activated carbon, a treatment technique Louisville Water already uses to address many water quality conditions. Currently, our scientists are researching how effective this strategy is in removing PFAS compounds under water quality conditions at both of our treatment plants. We also continue to monitor the Ohio River and the aquifer to determine whether PFAS levels vary based on seasonal patterns or with other water conditions.

PFAS travels into the Ohio River from a wide range of activities: manufacturing facilities producing or using products containing PFAS chemicals, publicly owned wastewater treatment plants, urban and even agricultural runoff. Louisville Water continues to research advanced treatment options to reduce levels even lower than what we currently detect. One of the options we are evaluating is using powdered activated carbon, a treatment technique Louisville Water already uses to address many water quality conditions. Currently, our scientists are researching how effective this strategy is in removing PFAS compounds under water quality conditions at both of our treatment plants. We also continue to monitor the Ohio River and the aquifer to determine whether PFAS levels vary based on seasonal patterns or with other water conditions.

Louisville Water also supports actions to minimize these contaminants entering our source water. We are actively working with leaders and industry peers on approaches to limit PFAS getting into drinking water and to provide financial help to drinking water utilities to meet the treatment challenges presented by PFAS in their source water.

Research and innovation never stop at Louisville Water. Protecting the public’s health is at the core of our mission. You can learn more about your drinking water in the Annual Water Quality Report. We love to talk about our drinking water, and you can always contact us.

You can also check out the EPA’s section on PFAS.