The Louisville Water Company we know today with a reputation for delivering high-quality, reliable drinking water to nearly a million people daily, began in 1860 with two main goals: providing an abundant (and healthier) water source (instead of well water) and providing fire protection.

The Louisville Water Company we know today with a reputation for delivering high-quality, reliable drinking water to nearly a million people daily, began in 1860 with two main goals: providing an abundant (and healthier) water source (instead of well water) and providing fire protection.

The “quest for pure water” was critical in Louisville. During the early 1800s, the city was dubbed the “graveyard of the west” because of its rampant cases of cholera. While the public didn’t necessarily see the need for cleaner water, the first engineers of what was then known as Water Works, had the foresight to build a strong foundation for the company.

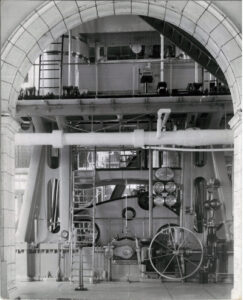

Chief engineer, Theodore Scowden, hired Charles Hermany, who shared his vision for grand and elegant appearances for the buildings and properties where the work would take place to produce and pump the water. Hermany left an indelible mark in his 50 years with Louisville Water. He led the way in designing the Louisville Water Tower, now the oldest ornamental standing water tower in the country, in addition to Original Pumping Station No. 1, and the Crescent Hill Reservoir & Gatehouse which opened in 1879.

Water Works pumped water to its first 512 customers on October 18, 1860. Well before microscopes were invented and scientists developed the “germ theory”, Hermany was on the right track. His leadership and innovative ideas helped put Louisville Water on the map when it came to the science of water.

1866: Chief Engineer Charles Hermany began the quest for pure water by declaring his desire to filter the muddy Ohio River water

1866: Chief Engineer Charles Hermany began the quest for pure water by declaring his desire to filter the muddy Ohio River water- 1879: Crescent Hill Reservoir opened to allow additional mud to settle from river water; designed to hold 110 million gallons of water

- 1893: Hermany-Leavitt steam engine pump constructed

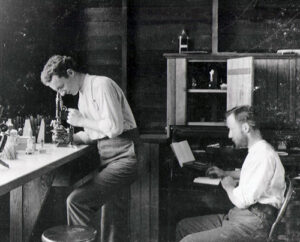

- 1896: George Warren Fuller, the “father of sanitary engineering”, conducted landmark filtration experiments at Louisville Water.

- Louisville Water spent approximately $43,000 on the experiments. Today, that would be equivalent to roughly $1.6 million. Source: Louisville Water Archive Specialist Jay Ferguson

Fuller’s experiments occurred on the same property where the Louisville Water Tower and Original Pumping Station No. 1 still stand. As chief chemist and bacteriologist, Fuller supervised the rapid sand-filtration studies while doing his own research. He concluded that settling the water in a reservoir followed by coagulation and filtration would create a cleaner water supply.

Fuller’s experiments occurred on the same property where the Louisville Water Tower and Original Pumping Station No. 1 still stand. As chief chemist and bacteriologist, Fuller supervised the rapid sand-filtration studies while doing his own research. He concluded that settling the water in a reservoir followed by coagulation and filtration would create a cleaner water supply.

- 1909: Crescent Hill Water Treatment Plant opened

- 1957: Anthracite coal added to sand and gravel filters in the filtration process

- 1997: Louisville Water trademarked its drinking water as Louisville Pure Tap®

1999: A single riverbank filtration collector well was built at the B.E. Payne Water Treatment Plant in Prospect

1999: A single riverbank filtration collector well was built at the B.E. Payne Water Treatment Plant in Prospect- 2009: Crescent Hill Water Treatment Plant phased gravel out of the filtration process

- 2010: Completed the riverbank filtration project at B.E. Payne; the first of its kind in the world

- Louisville Water tests Louisville Pure Tap® 200+ every day

Louisville Water built on George Warren Fuller’s work by making significant advances in using the riverbank’s natural sand and gravel filtering processes to remove contaminants from water before it’s pumped into a treatment plant. This is what we call riverbank filtration. Four collector wells, capped at ground level, are connected to a filtration tunnel by a 4-foot diameter pipe. Water flows by gravity from the aquifer to the wells and into the tunnel. Kay Ball, Louisville Water’s former program manager for advanced treatment technologies, said not only did the process provide an additional barrier against contaminants but it also provided a more stable incoming water temperature, which results in fewer main breaks.

The riverbank filtration project earned the Outstanding Civil Engineering Award in 2011.

The riverbank filtration project earned the Outstanding Civil Engineering Award in 2011.

Louisville Water consistently strives for excellence and looks for new opportunities to elevate its services and its impact, but the company maintains immense pride in its history and carries that forward.

In 2014, the past and present blended perfectly with the grand opening of the WaterWorks Museum housed inside the Original Pumping Station No. 1.

How many utilities can say they have a museum? The museum highlights Louisville Water’s archive of historic photographs, films, and memorabilia, some of which date back to 1860.

How many utilities can say they have a museum? The museum highlights Louisville Water’s archive of historic photographs, films, and memorabilia, some of which date back to 1860.

If there is one year that globally impacted everyone, it was 2020. COVID-19 forced Louisville Water, like many other companies, to reevaluate how to manage daily operations. Providing high-quality water was paramount amid a public health crisis, but keeping our employees safe in the process was equally critical. COVID caused financial hardships for families across America, prompting Louisville Water to create the Drops of Kindness℠ customer assistance program.

In July of that same year, Louisville Water achieved a milestone only a few utilities in the United States had accomplished at the time. Our proactive work for decades allowed us to remove all our known lead service lines that deliver drinking water. In all, Louisville Water has removed approximately 74,000 public lead service lines installed between 1860 and 1936. Helping lead the way in eliminating risks for lead in drinking water, scientists at Louisville Water took it a step further and invented Pure Spout®. The new-to-market product is a low-cost solution to replace existing water fountain spouts with a filter designed specifically to reduce levels of lead. It’s aimed at protecting students at public schools with aging infrastructure. Pure Spout achieved local and national recognition in 2024.

Also that year, Louisville Water publicly rolled out the WaterPro Water Leak Protection Plan℠. We are the first public utility to develop and offer this kind of service to customers. WaterPro provides peace of mind and financial relief from excess water charges caused by undetected leaks in homeowners’ plumbing.

As Louisville Water continues to embrace new technology and works to expand its footprint, our commitment is rooted in one of the very reasons the company was founded – public health. Three awards in 2025 reaffirmed our commitment. The Partnership for Safe Water recognized the Crescent Hill Water Treatment Plant for maintaining the Excellence in Water Treatment Award for 10 consecutive years. The plant is one of 19 in the country to achieve this prestigious award level. Both the Crescent Hill and B.E. Payne treatment plants received the 25-year Directors Award.

As Louisville Water continues to embrace new technology and works to expand its footprint, our commitment is rooted in one of the very reasons the company was founded – public health. Three awards in 2025 reaffirmed our commitment. The Partnership for Safe Water recognized the Crescent Hill Water Treatment Plant for maintaining the Excellence in Water Treatment Award for 10 consecutive years. The plant is one of 19 in the country to achieve this prestigious award level. Both the Crescent Hill and B.E. Payne treatment plants received the 25-year Directors Award.

“These longevity awards are a testament to our culture of continuous improvement. They are the byproduct of all the hardworking operators, engineers, and scientists who remain dedicated to the mission of public health and water treatment excellence,” said Manager of Water Quality and Compliance Chris Bobay.